Table of contents

Background

1.Introduction

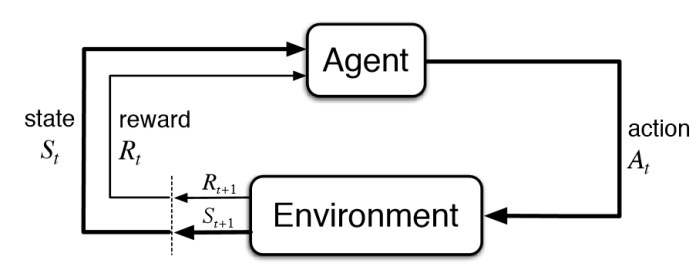

2.MDP

3. Planning by Dynamic Programming

4. model-free prediction

5 Model-free control

6 Value function approximation

7 Policy gradient methods

8.Integrating Learning and Planning

9. Exploration and Exploitation

10. Case Study: RL in Classic Games

Background

I started learning Reinforcement Learning 2018, and I first learn it from the book “Deep Reinforcement Learning Hands-On” by Maxim Lapan, that book tells me some high level concept of Reinforcement Learning and how to implement it by Pytorch step by step. But when I dig out more about Reinforcement Learning, I find the high level intuition is not enough, so I read the Reinforcement Learning An introduction by S.G, and following the courses Reinforcement Learning by David Silver, I got deeper understanding of RL. For the code implementation of the book and course, refer this Github repository.

Here is some of my notes when I taking the course, for some concepts and ideas that are hard to understand, I add some my own explanation and intuition on this post, and I omit some simple concepts on this note, hopefully this note will also help you to start your RL tour.

1.Introduction

RL feature

- reward signal

- feedback delay

- sequence not i.i.d

- action affect subsequent data

Why using discount reward?

- mathematically convenient

- avoids infinite returns in cyclic Markov processes

- we are not very confident about our prediction of reward, maybe we we only confident about some near future steps.

- human shows preference for immediate reward

- it is sometimes possible to use undiscounted reward

2.MDP

In MDP, reward is action reward, not state reward!

\(R_s^a=E[R_{t+1}|S_t=s,A_t=a]\)

Bellman Optimality Equation is non-linear , so we solve it by iteration methods.

3. Planning by Dynamic Programming

planning(clearly know the MDP(model) and try to find optimal policy)

prediction: given of MDP and policy, you output the value function(policy evaluation)

control: given MDP, output optimal value function and optimal policy(solving MDP)

-

policy evaluation

-

policy iteration

-

policy evaluation(k steps to converge)

-

policy improvement

if we iterate policy once and once again and the MDP we already know, we will finally get the optimal policy(proved). so the policy iteration solve the MDP.

-

value iteration

-

value update (1 step policy evaluation)

-

policy improvement(one step greedy based on updated value)

iterate this also solve the MDP

asynchronous dynamic programming

- in-place dynamic programming(update the old value with new value immediately, not wait for all states new value)

- prioritized sweeping(based on value iteration error)

- real-time dynamic programming(run the game)

4. model-free prediction

model-free by sample

Monte-Carlo learning

every update of Monte-Carlo learning must have full episode

-

First-Visit Monte-Carlo policy evaluation

just run the agent following the policy the first time that state s is visited in an episode and do following calculation

\(N(s)\gets N(s)+1 \\

S(s)\gets S(s)+G_t \\

V(s)=S(s)/N(s) \\

V(s)\to v_\pi \quad as \quad N(s) \to \infty\)

-

Every-Visit Monte-Carlo policy evaluation

just run the agent following the policy the every time(maybe there is a loop, a state can be visited more than one time) that state s is visited in an episode

Incremental mean

\(\begin{align}

\mu_k &= \frac{1}{k}\sum_{j=1}^k x_j \\

&=\frac{1}{k}(x_k + \sum_{j=1}^{k-1} x_j) \\

&= \frac{1}{k}(x_k + (k-1)\mu_{k-1}) \\

&= \mu_{k-1}+\frac{1}{k}(x_k - \mu_{k-1})

\end{align}\)

so by the incremental mean:

\(N(S_t)\gets N(S_t)+1 \\

V(S_t)\gets V(S_t)+\frac{1}{N_t}(G_t-v(S_t)) \\\)

In non-stationary problem, it can be useful to track a running mean, i.e. forget old episodes.

\(V(S_t)\gets V(S_t)+\alpha(G_t-V(S_t))\)

Temporal-Difference Learning

learn form incomplete episodes, it gauss the reward.

\(V(S_t)\gets V(S_t)+\alpha(G_t-V(S_t)) \\

V(s_t)\gets V(S_t)+\alpha(R_{t+1}+\gamma V(S_{t+1}) - V(S_t))\)

TD target: $G_t=R_{t+1}+\gamma V(S_{t+1})$ TD(0)

TD error: $\delta_t = R_{t+1}+\gamma V(S_{t+1}) -V(S_t)$

TD($\lambda$)—balance between MC and TD

Let TD target look $n$ steps into the future, if $n$ is very large and the episode is terminal, then it’s Monte-Carlo

\(\begin{align}

G_t^{(n)}&=R_{t+1}+\gamma R_{t+2}+ ... + \gamma^{n-1} R_{t+n} + \gamma^nV(S_{t+n}) \\

V(S_t)&\gets V(S_t)+\alpha(G_t-V(S_t))

\end{align}\)

Averaging n-step returns—forward TD($\lambda$)

\(\begin{align}

G_t^{\lambda} &= (1-\lambda)\sum_{n=1}^\infty \lambda^{n-1} G_t^{(n)} \\

V(S_t)&\gets V(S_t)+\alpha(G_t^\lambda-V(S_t))

\end{align}\)

Eligibility traces, combine frequency heuristic and recency heuristic

\(\begin{align}

E_0(s) &= 0 \\

E_t(s) &= \gamma \lambda E_{t-1}(s) + 1(S_t=s)

\end{align}\)

TD($\lambda$)—TD(0) and $\lambda$ decayed Eligibility traces —backward TD($\lambda$)

\(\begin{align}

\delta_t &= R_{t+1}+\gamma V(S_{t+1}) -V(S_t) \\

V(s) &\gets V(s)+\alpha \delta_tE_t(s)

\end{align}\)

if the updates are offline (means in one episode, we always use the old value), then the sum of forward TD($\lambda$) is identical to the backward TD($\lambda$)

\(\sum_{t=1}^T \alpha \delta_t E_t(s) = \sum_{t=1}^T \alpha(G_t^\lambda - V(S_t))1(S_t=s)\)

5 Model-free control

$\epsilon-greedy$ policy add exploration to make sure we are improving our policy and explore the ervironment.

On policy Monte-Carlo control

for every episode:

- policy evaluation: Monte-Carlo policy evaluation $Q\approx q_\pi $

- policy improvement: $\epsilon-greedy$ policy improvement based on $Q(s,a)$

Greedy in the limit with infinite exploration (GLIE) will find optimal solution.

GLIE Monte-Carlo control

for the $k$th episode, set $\epsilon \gets 1/k$ , finally $\epsilon_k$ reduce to zero, and it will get the optimal policy.

On-policy TD learning

Sarsa

\(Q(S,A) \gets Q(S,A)+\alpha (R+ \gamma Q(S',A')-Q(S,A))\)

On-Policy Sarsa:

for every time-step:

- policy evaluation: Sarsa, $Q\approx q_\pi $

- policy improvement: $\epsilon-greedy$ policy improvement based on $Q(s,a)$

forward n-step Sarsa —>Sarsa($\lambda$) just like TD($\lambda$)

Eligibility traces:

\(\begin{align}

E_0(s,a) &= 0 \\

E_t(s,a) &= \gamma \lambda E_{t-1}(s,a) + 1(S_t=s,A_t=a)

\end{align}\)

backward Sarsa($\lambda$) by adding eligibility traces

and every time step for all $(s,a)$ do following:

\(\begin{align}

\delta_t &= R_{t+1}+\gamma Q(S_{t+1},A_{t+1}) -Q(S_t,A_t) \\

Q(s,a) &\gets Q(s,a)+\alpha \delta_tE_t(s,a)

\end{align}\)

The intuition of this that the current state action pair reward and value influence all other state action pairs, but it will influence the most frequent and recent pair more. and the $\lambda$ shows how much current influence others. if you only use one step Sarsa, every you get reward, it only update one state action pair, so it is slower. For more, refer Gridworld example on course-5.

Off-policy learning

Importance sampling

\[\begin{align}

E_{X~\sim P}[f(X)] &= \sum P(X)f(X) \\

&=\sum Q(X) \frac{P(X)}{Q(X)} f(X)

&= E_{X ~\sim Q}\left[\frac{P(X)}{Q(X)} f(X)\right]

\end{align}\]

Importance sampling for off-policy TD

\(V(s_t) \gets V(S_t) + \alpha \left(\frac{\pi(A_t|S_t)}{\mu(A_t|S_t)}(R_{t+1}+\gamma V(S_{t+1})-V(s_t)\right)\)

Q-learning

| Next action is chosen using behavior policy(the true behavior) $A_{t+1} ~\sim \mu(. |

S_t)$ |

but consider alternative successor action(our target policy) $A’ \sim \pi(.|S_t)$

\(Q(S,A) \gets Q(S,A)+\alpha (R_{t+1} + \gamma Q(S_{t+1},A')-Q(S,A))\)

Here has something may hard to understand, so I explain it. no matter what action we actually do(behave) next, we just update Q according our target policy action, so finally we got the Q of target policy $\pi$.

Off-policy control with Q-Learning

-

the target policy is greedy w.r.t Q(s,a)

\(\pi(S_{t+1})=\underset{a'}{\arg\max} Q(S_{t+1},a)\)

-

the behavior policy $\mu$ is e.g. $\epsilon -greedy$ w.r.t. Q(s,a) or maybe some totally random policy, it doesn’t matter for us since it is off-policy, and we only evaluate Q on $\pi$.

\[Q(S,A) \gets Q(S,A)+\alpha (R+ \gamma \max_{a'} Q(S',A')-Q(S,A))\]

and Q-learning will converges to the optimal action-value function $Q(s,a) \to q_*(s,a)$

Q-learning can be used in off-policy learning, but it also can be used in on-policy learning!

For on-policy, if you using $\epsilon -greedy$ policy update, Sarsa is a good on-policy method, but you use Q-learning is fine since $\epsilon -greedy$ is similar to max Q policy, so you can make sure you explore most of policy action, so it is also efficient.

6 Value function approximation

Before this lecture, we talk about tabular learning since we have to maintain a Q table or value table etc.

Introduction

why

- state space is large

- continuous state space

Value function approximation

\[\begin{align}

\hat{v}(s,\pmb{w}) &\approx v_\pi(s) \\

\hat{q}(s,a,\pmb{w})&\approx q_\pi(s,a)

\end{align}\]

Approximator

- non-stationary (state values are changing since policy is changinng)

- non-i.i.d. (sample according policy)

Incremental method

Basic SGD for Value function approximation

- Stochastic Gradient descent

- feature vectors

\[x(S) = \begin{pmatrix}

x_1(s) \\

\vdots \\

x_n(s)

\end{pmatrix}\]

-

linear value function approximation

\(\begin{align}

\hat{v}(S,\pmb{w}) &= \pmb{x}(S)^T \pmb{w} = \sum_{j=1}^n \pmb{x}_j(S) \pmb{w}_j\\

J(\pmb {w}) &= E_\pi\left[(v_\pi(S)-\hat{v}(S,\pmb{w}))^2\right] \\

\Delta\pmb{w}&=-\frac{1}{2} \alpha \Delta_w J(\pmb{w}) \\

&=\alpha E_\pi \left[(v_\pi(S)-\hat{v}(S,\pmb{w})) \Delta_{\pmb{w}}\hat{v}(S,\pmb{w})\right] \\

\Delta\pmb{w}&=\alpha (v_\pi(S)-\hat{v}(S,\pmb{w})) \Delta_{\pmb{w}}\hat{v}(S,\pmb{w}) \\

& = \alpha (v_\pi(S)-\hat{v}(S,\pmb{w}))\pmb{x}(S)

\end{align}\)

-

Table lookup feature

table lookup is a special case of linear value function approximation, where w is the value of individual state.

\[x(S) = \begin{pmatrix}

1(S=s_1)\\

\vdots \\

1(S=s_n)

\end{pmatrix}\\

\hat{v}(S,w) = \begin{pmatrix}

1(S=s_1)\\

\vdots \\

1(S=s_n)

\end{pmatrix}.\begin{pmatrix}

w_1\\

\vdots \\

w_n

\end{pmatrix}\]

Incremental prediction algorithms

How to supervise?

-

For MC, the target is the return $G_t$

\(\Delta w = \alpha (G_t-\hat{v}(S_t,\pmb w))\Delta_w \hat{v}(S_t,w)\)

-

For TD(0), the target is the TD target $R_{t+1} + \gamma \hat{v}(S_{t+1},\pmb{w})$

\(\Delta w = \alpha (R_{t+1} + \gamma \hat{v}(S_{t+1},\pmb{w})-\hat{v}(S_t,\pmb w))\Delta_w \hat{v}(S_t,w)\)

here should notice that the TD target also has $\hat{v}(S_{t+1},\pmb{w})$, it contains w, but we do not calculate gradient of it, we just trust target at each time step, we only look forward, rather than look forward and backward at the same time. Otherwise it can not converge.

-

For $TD(\lambda)$ , the target is $\lambda-return G_t^\lambda$

$$

\begin{align}

\Delta\pmb{w} &= \alpha (G_t^\lambda-\hat{v}(S_t,\pmb w))\Delta_w \hat{v}(S_t,w) \

\end{align}

\(for backward view of Linear $TD(\lambda)$:\)

\begin{align}

\delta_t&= R_{t+1} + \gamma \hat{v}(S_{t+1},\pmb{w})-\hat{v}(S_t,\pmb{w})

E_t &= \gamma \lambda E_{t-1} +\pmb{x}(S_t)

\Delta \pmb{w}&=\alpha \delta_t E_t

\end{align}

$$

here, unlike $E_t(s) = \gamma \lambda E_{t-1}(s) + 1(S_t=s)$ , we put $x(S_t)$ in $E_t$, so we don’t need remember all previous $x(S_t)$, note that in Linear TD, $\Delta \hat{v}(S_t,\pmb{w})$ is $x(S_t)$.

here the eligibility traces is the state features, so the most recent state(state feature) have more weight, unlike TD(0), this is update all previous states simultaneously and the weight of state decayed by $\lambda$.

Control with value function approximation

policy evaluation: approximate policy evaluation, $\hat{q}(.,.,\pmb{w}) \approx q_\pi$

policy improvement: $\epsilon - greedy$ policy improvement.

Action-value function approximation

\(\begin{align}

\hat{q}(S,A,\pmb{w}) &\approx q_\pi(S,A)\\

J(\pmb {w}) &= E_\pi\left[(q_\pi(S,A)-\hat{q}(S,A,\pmb{w}))^2\right] \\

\Delta\pmb{w}&=-\frac{1}{2} \alpha \Delta_w J(\pmb{w}) \\

&=\alpha (q_\pi(S,A)-\hat{q}(S,A,\pmb{w}))\Delta_{\pmb{w}}\hat{q}(S,A,\pmb{w})

\end{align}\)

Linear Action-value function approximation

\(\begin{align}x(S,A) &= \begin{pmatrix}

x_1(S,A)\\

\vdots \\

x_n(S,A)

\end{pmatrix} \\

\hat{q}(S,A,\pmb{w}) &= \pmb{x}(S,A)^T \pmb{w} = \sum_{j=1}^n \pmb{x}_j(S,A) \pmb{w}_j\\

\Delta\pmb{w}&=\alpha (q_\pi(S,A)-\hat{q}(S,A,\pmb{w}))x(S,A)

\end{align}\)

The target is similar as value update, I’m lazy and do not write it down, you can refer it on book.

TD is not guarantee converge

convergence of gradient TD learning

Convergence of Control Algorithms

Batch reinforcement learning

motivation: try to fit the experiences

- given value function approximation $\hat{v}(s,\pmb{w} \approx v_\pi(s))$

- experience$\mathcal{D} $ consisting of$\langle state,value \rangle$ pairs:

\[\mathcal{D} = \{\langle s_1,v_1^\pi\rangle\,\langle s_2,v_2^\pi\rangle\,...,\langle s_n,v_n^\pi\rangle\}\]

- Least squares minimizing sum-squares error

\(\begin{align}

LS(\pmb{w})&=\sum_{t=1}^T(v_t^\pi -\hat{v}(s_t,\pmb{w}))^2 \\

&=\mathbb{E}_\mathcal{D}\left[(v^\pi-\hat{v}(s,\pmb{w}))^2\right]

\end{align}\)

SGD with experience replay(de-correlate states)

-

sample state, vale form experience

\(\langle s,v^\pi\rangle \sim \mathcal{D}\)

-

apply SGD update

\[\Delta\pmb{w} = \alpha (v^\pi-\hat{v}(s,\pmb{w}))\Delta_{\pmb{w}}\hat{v}(s,\pmb{w})\]

Then converge to least squares solution

DQN (experience replay + Fixed Q-targets)(off-policy)

-

Take action $a_t$ according to $\epsilon - greedy$ policy to get experience $(s_t,a_t,r_{t+1},s_{t+1})$ store in $\mathcal{D}$

-

Sample random mini-batch of transitions $(s,s,r,s’)$

-

compute Q-learning targets w.r.t. old, fixed parameters $w^-$

-

optimize MSE between Q-network and Q-learning targets.

\(\mathcal{L}_i(\mathrm{w}_i) = \mathbb{E}_{s,a,r,s' \sim \mathcal{D}_i}\left[\left(r+\gamma \max_{a'} Q(s',a';\mathrm{w^-})-Q(s,a,;\mathrm{w}_i)\right)^2\right]\)

-

using SGD update

On-linear Q-learning hard to converge, so why DQN converge?

- experience replay de-correlate state make it more like i.i.d.

- Fixed Q-targets make it stable

Least square evaluation

if the approximation function is linear and the feature space is small, we can solve the policy evaluation by least square directly.

- policy evaluation: evaluation by least squares Q-learning

- policy improvement: greedy policy improvement.

7 Policy gradient methods

Introduction

policy-based reinforcement learning

directly parametrize the policy

\(\pi_\theta(s,a) = \mathcal(P)[a|s,\theta]\)

advantages:

- better convergence properties

- effective in high-dimensional or continuous action spaces

- can learn stochastic policies

disadvantages:

- converge to a local rather then global optimum

- evaluating a policy is typically inefficient and high variance

policy gradient

Let $J(\theta)$ be policy objective function

find local maximum of policy objective function(value of policy)

\(\Delta \theta = \alpha \Delta_\theta J(\theta)\)

where $\Delta_\theta J(\theta)$ is the policy gradient

\(\Delta_\theta J(\theta) = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial\theta_1 } \\

\vdots \\

\frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial\theta_n }

\end{pmatrix}\)

Score function trick

\(\begin{align}

\Delta_\theta\pi(s,a) &= \pi_\theta \frac{\Delta_\theta(s,a)}{\pi_\theta(s,a)} \\

&=\pi_\theta(s,a)\Delta_\theta \log\pi_\theta(s,a)

\end{align}\)

The score function is $\Delta_\theta \log\pi_\theta(s,a)$

policy

- Softmax policy for discrete actions

- Gaussian policy for continuous action spaces

for one-step MDPs apply score function trick

\(\begin{align}

J(\theta) & = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}[r] \\

& = \sum_{s\in \mathcal{S}} d(s) \sum _{a\in \mathcal{A}} \pi_\theta(s,a)\mathcal{R}_{s,a}\\

\Delta J(\theta) & = \sum_{s\in \mathcal{S}} d(s) \sum _{a\in \mathcal{A}} \pi_\theta(s,a)\Delta_\theta\log\pi_\theta(s,a)\mathcal{R}_{s,a} \\

& = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}[\Delta_\theta\log\pi_\theta(s,a)r]

\end{align}\)

Policy gradient theorem

the policy gradient is

\(\Delta_\theta J(\theta)= \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}[\Delta_\theta\log\pi_\theta(s,a)Q^{\pi_\theta}(s,a)]\)

Monte-Carlo policy gradient(REINFORCE)

using return $v_t$ as an unbiased sample of $Q^{\pi_\theta}(s_t,a_t)$

\(\Delta\theta_t = \alpha\Delta_\theta\log\pi_\theta(s,a)v_t\\

v_t = G_t = r_{t+1}+\gamma r_{t+2}+\gamma^3 r_{t+3}...\)

pseudo code

function REINFORCE

Initialize $\theta$ arbitrarily

for each episode $ { s_1,a_1,r_2,…,s_{T-1},a_{T-1},R_T } \sim \pi_\theta$ do

for $t=1$ to $T-1$ do

$\theta \gets \theta+\alpha\Delta_\theta\log\pi_\theta(s,a)v_t$

end for

end for

return $\theta$

end function

REINFORCE has the high variance problem, since it get $v_t$ by sampling.

Actor-Critic policy gradient

Idea

use a critic to estimate the action-value function

\(Q_w(s,a) \approx Q^{\pi_\theta}(s,a)\)

Actor-Critic algorithm follow an approximate policy gradient

\(\Delta_\theta J(\theta) \approx \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}[\Delta_\theta\log\pi_\theta(s,a)Q_w(s,a)] \\

\Delta \theta= \alpha \Delta_\theta\log\pi_\theta(s,a)Q_w(s,a)\)

Action value actor-Critic

Using linear value fn approx. $Q_w(s,a) = \phi(s,a)^Tw$

- Critic Updates w by TD(0)

- Actor Updates $\theta$ by policy gradient

function QAC

Initialize $s, \theta$

Sample $a \sim \pi_\theta$

for each step do

Sample reward $r=\mathcal{R}_s^a$; sample transition $s’ \sim \mathcal{P}_s^a$,.

Sample action $a’ \sim \pi_\theta(s’,a’)$

$\delta = r + \gamma Q_w(s’,a’)- Q_w(s,a)$

$\theta = \theta + \alpha \Delta_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s,a) Q_w(s,a)$

$w \gets w+\beta \delta\phi(s,a)$

$a \gets a’, s\gets s’$

end for

end function

So it seems that Value-based learning is a spacial case of actor-critic, since the greedy function based on Q is one spacial case of policy gradient, when we set the policy gradient step size very large, then the probability of the action which max Q will close to 1, and the others will close to 0, that is what greedy means.

Reducing variance using a baseline

-

Subtract a baseline function $B(s)$ from the policy gradient

-

This can reduce variance, without changing expectation

\(\begin{align}

\mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} [\Delta_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s,a)B(s)] &= \sum_{s \in \mathcal{S}}d^{\pi_\theta}(s)\sum_a \Delta_\theta \pi_\theta(s,a)B(s)\\

&= \sum_{s \in \mathcal{S}}d^{\pi_\theta}(s)B(s)\Delta_\theta \sum_{a\in \mathcal{A}} \pi_\theta(s,a)\\

& = \sum_{s \in \mathcal{S}}d^{\pi_\theta}(s)B(s)\Delta_\theta (1) \\

&=0

\end{align}\)

-

a good baseline is the state value function $B(s) = V^{\pi_\theta}(s)$

-

So we can rewrite the policy gradient using the advantage function $A^{\pi_\theta}(s,a)$

\(A^{\pi_\theta}(s,a) = Q^{\pi_\theta}(s,a) - V^{\pi_\theta}(s) \\

\Delta_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}[\Delta_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s,a)A^{\pi_\theta}(s,a)]\)

Actually, by using advantage function, we get rid of the variance between states, and it will make our policy network more stable.

So how to estimate the advantage function? you can using two network to estimate Q and V respectively, but it is more complicated. More commonly used is by bootstrapping.

\[\delta^{\pi_\theta} = r + \gamma V^{\pi_\theta}(s')-V^{\pi_\theta}(s)\]

-

TD error is an unbiased estimate(sample) of the advantage function

\(\begin{align}

\mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta} & = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}[r + \gamma V^{\pi_\theta}(s')|s,a] - V^{\pi_\theta}(s) \\

& = Q^{\pi_\theta}(s,a)-V^{\pi_\theta}(s) \\

& = A^{\pi_\theta}(s,a)

\end{align}\)

-

So

\(\Delta_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi_\theta}[\Delta_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s,a)\delta^{\pi_\theta}]\)

-

In practice, we can use an approximate TD error for one step

\(\delta_v = r + \gamma V_v(s')-V_v(s)\)

-

this approach only requires one set of critic parameters for v.

For Critic, we can plug in previous used methods in value approximation, such as MC, TD(0),TD($\lambda$) and TD($\lambda$) with eligibility traces.

-

MC policy gradient, $\mathrm{v}_t$ is the true MC return.

\(\Delta \theta = \alpha(\mathrm{v}_t - V_v(s_t))\Delta_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s_t,a_t)\)

-

TD(0)

\(\Delta \theta = \alpha(r + \gamma V_v(s_{t+1})-V_v(s_t))\Delta_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s_t,a_t)\)

-

TD($\lambda$)

\(\Delta \theta = \alpha(\mathrm{v}_t^\lambda + \gamma V_v(s_{t+1})-V_v(s_t))\Delta_\theta \log \pi_\theta(s_t,a_t)\)

-

TD($\lambda$) with eligibility traces (backward-view)

\(\begin{align}

\delta & = r_{t+1} + \gamma V_V(s_{t+1}) -V_v(s_t) \\

e_{t+1} &= \lambda e_t + \Delta_\theta\log \pi_\theta(s,a) \\

\Delta \theta&= \alpha \theta e_t

\end{align}\)

For continuous action space, we use Gauss to represent our policy, but Gauss is noisy, so it’s better to use deterministic policy(by just picking the mean) to reduce noise and make it easy to converge. This turns out the deterministic policy gradient(DPG) algorithm.

Deterministic policy gradient(off-policy)

Deterministic policy:

\(a_t = \mu(s_t|\theta^\mu)\)

Q network parametrize by $\theta^Q$ ,the distribution of states under behavior policy is $\rho^\beta$

\(\begin{align}

L(\theta^Q) &= \mathbb{E}_{s_t \sim \rho^\beta, a_t \sim \beta,r_t\sim E}[(Q(s_t,a_t|\theta^Q)-y_t)^2] \\

y_t & = r(s_t,a_t)+\gamma Q(s_{t+1},\mu(s_{t+1})|\theta^Q)

\end{align}\)

policy network parametrize by $\theta^\mu$

\(\begin{align}

J(\theta^\mu) & = \mathbb{E}_{s \sim \rho^\beta}[Q(s,a| \theta^Q)|_{s=s_t,a=\mu(s_t|\theta^\mu)}] \\

\Delta_{\theta^\mu}J &\approx \mathbb{E}_{s \sim \rho^\beta}[\Delta_{\theta_\mu} Q(s,a| \theta^Q)|_{s=s_t,a=\mu(s_t|\theta^\mu)}] \\

& = \mathbb{E}_{s \sim \rho^\beta}[\Delta Q(s,a| \theta^Q|_{s=s_t,a=\mu(s_t)}\Delta_{\theta_\mu}\mu(s|\theta^\mu)|s=s_t]

\end{align}\)

to make training more stable, we use target network for both critic network and actor network, and update them by soft update:

\(soft\; update\left\{

\begin{aligned}

\theta^{Q'} & \gets \tau\theta^Q+(1-\tau)\theta^{Q'} \\

\theta^{\mu'} & \gets \tau\theta^\mu+(1-\tau)\theta^{\mu'} \\

\end{aligned}

\right.\)

and we set $\tau$ very small to update parameters smoothly, e.g. $\tau = 0.001$.

In addition, we add some noise to deterministic action when we are exploring the environment to get experience.

\(\mu'(s_t) = \mu(s_t|\theta_t^\mu)+\mathcal{N}_t\)

where $\mathcal{N}$ is the noise, it can be chosen to suit the environment, e.g. Ornstein-Uhlenbeck noise.

8.Integrating Learning and Planning

Introduction

model-free RL

- no model

- Learn value function(and or policy) from experience

model-based RL

- learn a model from experience

- plan value function(and or policy) from model

Model $\mathcal{M} = \langle \mathcal{P}\eta, \mathcal{R}\eta \rangle$

\(S_{t+1} \sim \mathcal{P}_\eta(s_{t+1}|s_t,A_t) \\

R_{t+1} = \mathcal{R}_\eta(R_{t+1}|s_t,A_t)\)

Model learning from experience ${S_1,A_1,R_2,…,S_T}$ bu supervised learning

\(S_1, A_1 \to R_2, S_2 \\

S_2, A_2 \to R_3, S_3 \\

\vdots \\

S_{T-1}, A_{T-1} \to R_T, S_T\)

- $s,a \to r$ is a regression problem

- $s,s \to s’$ is a density estimation problem

Planning with a model

Sample-based planning

- sample experience from model

- apply model-free RL to samples

- Monte-Carlo control

- Sarsa

- Q-learning

Performance of model-based RL is limited to optimal policy for approximate MDP

Integrated architectures

Integrating learning and planning—–Dyna

- Learning a model from real experience

- Learn and plan value function (and/or policy) from real and simulated experience

Simulation-Based Search

- Forward search select the best action by lookahead

- build a search tree withe the current state $s_t$ at the root

- solve the sub-MDP starting from now

Simulation-Based Search

- Simulate episodes of experience for now with the model

- Apply model-free RL to simulated episodes

- Monte-Carlo control $\to$ Monte-Carlo search

- Sarsa $\to$ TD search

Sample Monte-Carlo search

-

Given a model $\mathcal{M}_v$ and a simulation policy $\pi$

-

For each action $a \in \mathcal{A}$

-

Simulate K episodes from current(real) state $s_t$

\(\{s_t,a,R_{t+1}^k,S_{t+1}^k,A_{t+1}^k,...,s_T^k\}_{k=1}^K \sim \mathcal{M}_v,\pi\)

-

Evaluate action by mean return(Monte-Carlo evaluation)

\[Q(s_t,a) = \frac{1}{K}\sum_{k=1}^K G_t \overset{\text{P}}{\to} q_\pi(s_t,a)\]

-

Select current(real) action with maximum value

\(a_t = \underset{a \in \mathcal{A}}{\arg\max} Q(S_{t},a)\)

Monte-Carlo tree search

-

Given a model $\mathcal{M}_v$

-

Simulate K episodes from current(real) state $s_t$ using current simulation policy $\pi$

\(\{s_t,A_t^k,R_{t+1}^k,S_{t+1}^k,A_{t+1}^k,...,s_T^k\}_{k=1}^K \sim \mathcal{M}_v,\pi\)

-

Build a search tree containing visited states and actions

-

Evaluate states Q(s,a) by mean return of episodes from s,a

\(Q(s_t,a) = \frac{1}{N(s,a)}\sum_{k=1}^K \sum_{u=t}^T \mathbf{1}(s_u,A_u = s,a) G_u \overset{\text{P}}{\to} q_\pi(s_t,a)\)

-

After search is finished, select current(real) action with maximum value in search tree

\(a_t = \underset{a \in \mathcal{A}}{\arg\max} Q(S_{t},a)\)

-

Each simulation consist of two phases(in-tree, out-of-tree)

- Tree policy(improves): pick actions to maximise Q(s,a)

- Default policy(fixed): pick action randomly

Here we update Q on the whole sub-tree, not only the current state. And after every episode of searching, we improve the policy based on the new update value, then start a new searching. With the searching progress, we exploit on the direction which is more promise to success since we keep updating our searching policy to that direction. In addition, we also need to explore a little bit the other direction, so we can apply MCTS with which action has the max Upper Confidence Bound(UCT) , that is idea of AlphaZero.

Temporal-Difference Search

e.g. update by Sarsa

\(\Delta Q(S,A) = \alpha (R+\gamma Q(S',A') -Q(S,A))\)

and you can also use a function approximation for simulated Q.

Dyna-2

- long-term memory(real experience)—TD learning

- Short-term(working) memory(simulated experience)—TD search & TD learning

9. Exploration and Exploitation

way to exploration

- random exploration

- use Gaussian noise in continuous action space

- $\epsilon - greedy$, random on $\epsilon$ probability

- Softmax, select on action policy distribution

- optimism in the face of uncertainty———prefer to explore state/actions with highest uncertainty

- Optimistic Initialization

- UCB

- Thompson sampling

- Information state space

- Gittins indices

- Bayes-adaptive MDPS

State-action exploration vs. parameter exploration

Multi-arm bandit

Total regret

\(\begin{align}

L_t &= \mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{\tau=1}^t V^*-Q(a_\tau)\right] \\

& \sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}}\mathbb{E}[N_t(a)](V^*-Q(a)) \\

&=\sum_{a \in \mathcal{A}}\mathbb{E}[N_t(a)]\Delta a

\end{align}\)

Optimistic Initialization

- initialize Q(a) to high value

- Then act greedily

- turns out linear regret

$\epsilon - greedy$

decay $\epsilon - greedy$

- sub-linear regret(need know gaps), if you tune it very well and find it just on the gap, it is good, otherwise, it maybe bad.

the regret has a low bound, it is a log bound

The performance of any algorithm is determined by similarity between optimal arm and other arms

\(\lim_{t \to \infty}L_t \ge \log t\sum_{a|\Delta a>0} \frac{\Delta a}{KL(\mathcal{R}^a||\mathcal{R}^{a_*})}\)

Optimism in the Face of Uncertainty

Upper Confidence Bounds(UCB)

-

Estimate an upper confidence $U_t(a)$ for each action value

-

Such that $q(a) \leq Q_t(a)+U_t(a)$ with high probability

-

The upper confidence depend on the number of times N(s) has been sampled

-

Select action maximizing Upper Confidence Bounds(UCB)

\(A_t =\underset{a \in \mathcal{A}}{\arg\max} [Q(S_{t},a)+U_t(a)]\)

Theorem(Hoeffding’s Inequality)

let $x_1,…,X_t$ be i.i.d. random variables in[0,1], and let $\overline{X} = \frac{1}{\tau}\sum_{\tau=1}^tX_\tau$ be the sample mean. Then

\(\mathbb{P}[\mathbb{E}[X]> \overline{X}_t+u] \leq e^{-2tu^2}\)

we apply the Hoeffding’s Inequality to rewards of the bandit conditioned on selecting action a

\(\mathbb{P}[ Q(a)> Q(a)+U_t(a)] \leq e^{-2N_t(a)U_t(a)^2}\)

-

Pack a probability p that true value exceeds UCB

-

Then solve for $U_t(a)$

\(\begin{align}

e^{-2N_t(a)U_t(a)^2} = p \\ \\

U_t(a)=\sqrt{\frac{-\log p}{2N_t(a)}}

\end{align}\)

-

Reduce p as we observe more rewards, e.g. $p = t^{-4}$

\(U_t(a)=\sqrt{\frac{2\log t}{N_t(a)}}\)

-

Make sure we select optimal action as $t \to \infty$

This leads to the UCB1 algorithm

\(A_t =\underset{a \in \mathcal{A}}{\arg\max} \left[Q(S_{t},a)+\sqrt{\frac{2\log t}{N_t(a)}}\right]\)

The UCB algorithm achieves logarithmic asymptotic total regret

\(\lim_{t\to\infty}L_t \leq 8\log t\sum_{a|\Delta>0}\Delta a\)

Bayesian Bandits

Probability matching—Thompson sampling—optimal for one sample, but may not good for MDP.

define MDP on information state space

MDP

UCB

\(A_t =\underset{a \in \mathcal{A}}{\arg\max} [Q(S_{t},a)+U_t(S_t,a)]\)

R-Max algorithm

10. Case Study: RL in Classic Games

TBA.